In 1830, Michigan Territorial Governor Lewis Cass declared Wisconsin’s first Thanksgiving, more or less.

At that time, Wisconsin was a part of the vast Michigan Territory, which included present-day Michigan, Wisconsin, and parts of Minnesota and Illinois and where Thanksgiving had been recognized on every November 25th since 1824. All told, there were fewer than 32,000 settlers in the territory according to census figures.

Wisconsin would not become a state until 1848.

One of the most striking aspects of Wisconsin winters in the1830s was the extreme cold. Temperatures frequently dipped well below freezing, occasionally reaching frigid levels of -20 degrees Fahrenheit or lower. This intense cold posed numerous challenges for settlers who had to navigate their daily routines.

Wisconsin in 1830 had a significant presence of Native peoples including the Menominee, Ojibwe, HoChunk, Sauk, Fox and Potawatomi. While there were trade and other interactions between settlers and natives, tensions between some tribes and the newcomers were growing at this time, and the Black Hawk War between the United States and members of the Sauk, Fox and Kickapoos would begin in just a couple of years.

While the native tribes had developed their own methods of surviving the harsh winter months, relying on techniques such as ice fishing and snowshoeing to navigate the snowy landscapes, the settlers, many French explorers, often had to learn as new problems would present themselves.

Surviving the winter meant ensuring a stable supply of and fuel. Many households stored provisions during the more fruitful months to sustain them throughout the colder season. This included preserving meat and produce, as well as stocking firewood. Hunting and trapping were common practices, allowing settlers to supplement their food supplies.

If you think it takes too long to clear your subdivision of snow and ice, you’d have not survived the first Thanksgiving in Wisconsin. The lack of well-maintained roads made traveling in Wisconsin during the winter extremely difficult. Settlers primarily relied on horse-drawn sleighs or sleds to move through the snow-covered landscapes.

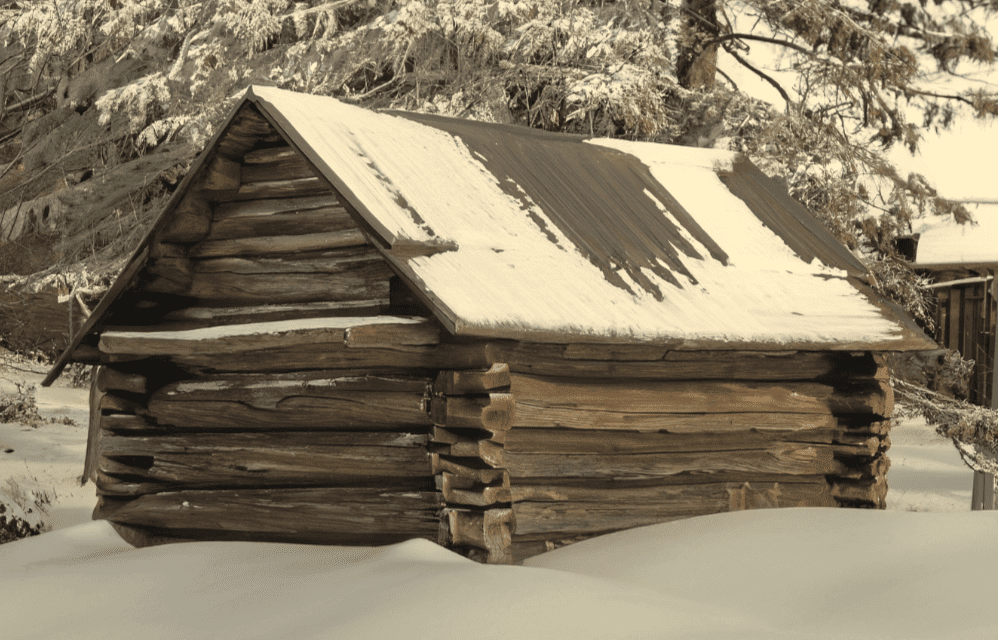

While the kids back from college may be whining this Thanksgiving over slow internet speeds and Grandma turning the heat up too high, the majority of settlers in Wisconsin during the 1830s lived in log cabins, which provided only some insulation against the cold weather.

Wood-burning stoves and fireplaces were essential for heating homes and providing warmth during the long winter nights. Settlers relied heavily on firewood for both heat and cooking. Families would near the hearth to stay warm, tell stories, and engage in simple activities to pass the time. For many Wisconsin families, this continues to be a Thanksgiving tradition.

Daily life for settlers in 1830s Wisconsin involved basic chores and tasks centered around survival. The few women in the region would have performed cooking, sewing, and other domestic work, while men focused on tending the livestock, repairing tools, and hunting or trapping for food. While most students here probably think they don’t get enough time off for Thanksgiving, education in the 1830s here was limited, with children receiving their education at home through informal means.

Due to the limited access to fresh produce during the winter, the diet of Wisconsin settlers in 1830 consisted primarily of preserved food, such as salted or smoked meat, dried fruits and vegetables, and pickled items. Staple crops like potatoes and grains that could be stored for longer periods formed the basis of many meals. If sweet potatoes were consumed, they most definitely were not topped with marshmallows.

The freezing temperatures in Wisconsin allowed for the harvesting of ice from lakes and rivers during the winter. Ice blocks were cut and stored in icehouses, providing a valuable resource for refrigeration during the warmer months when fresh food preservation was challenging.

Despite the hardships, Wisconsin settlers found ways to enjoy the winter season. Ice skating, sledding, and tobogganing were popular activities among both adults and children. Community gatherings, such as barn dances provided connections and entertainment during long winter evenings.

Hundreds of years before Black Friday sales and same day deliveries, Winters brought a heightened sense of self-sufficiency as settlers had to rely on their own resourcefulness and skills.

This meant repairing household items, crafting warm clothing, and finding ways to sustain themselves without relying on frequent visits to neighboring towns or cities.

Agriculture was limited during the winter months due to the frozen ground and harsh weather conditions. It is believed some settlers may have engaged in small-scale indoor agriculture, growing crops like winter wheat or maintaining small greenhouses produce fresh food year-round.

One thing is certain, while some may have feasted on a bit of game, perhaps even turkey, there was no hot dish of green bean casserole topped with crispy fried onions.

Overall, Wisconsin life in the winter of 1830 was characterized by isolation, resilience, a reliance on self-sufficiency and simmering tension between natives and settlers as the United States continued to expand Westward.

Facing extreme cold, limited food options, and challenging travel conditions, the new settlers adapted and eventually were able to shed themselves of the connection to Michigan. For this, we are grateful.

Happy Thanksgiving and go Packers.

The Wisconsin Historical Society is THE best place for more in-depth information about this and similar topics and we highly recommend you check out their extensive online archives and support them when you can.