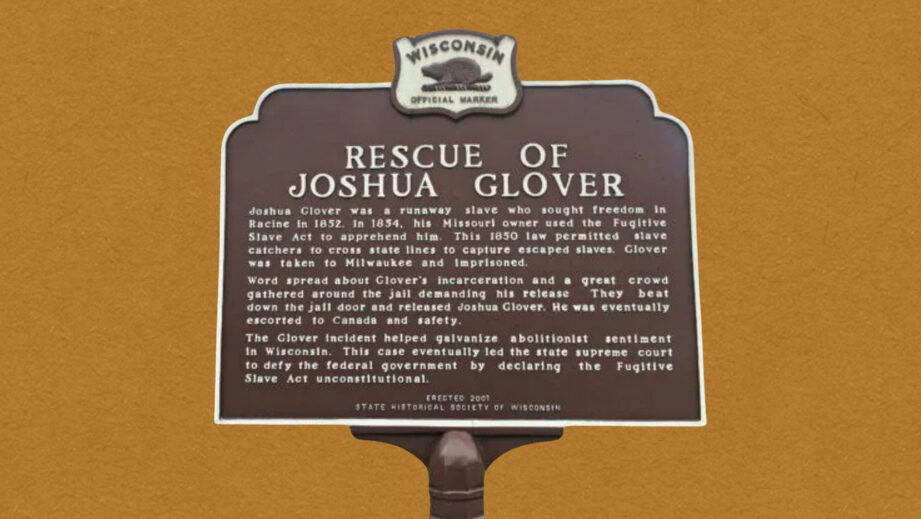

Joshua Glover’s story is a gritty testament to individual strength and collective defiance, a chapter of American history that unfolded in the tense years before the Civil War. It speaks to the terrible birth defect of our nation that was slavery, and Wisconsin’s role in putting an end to the practice in the United States.

Born into slavery in Missouri, likely between 1810 and 1830—precise dates vanish in the fog of bondage—Glover’s life took a sharp turn when he fled north in May 1852. Fleeing from the liberty-denying existence he endured at the sprawling 300-acre Prairie House Farm owned by Benammi Stone Garland in St. Louis, he crossed the Mississippi River, trekking roughly 300 miles to Racine, Wisconsin. There, he found work at the Sinclair and Rice Sawmill, owned by Duncan Sinclair, and settled into a modest cabin, tasting freedom for the first time.

But his fleeting liberty was threatened on March 10, 1854, when Garland, aided by federal marshals and St. Louis police, stormed Glover’s home. Betrayed by a friend, Nathan Turner, Glover was ambushed while playing cards, beaten unconscious, and hauled to Milwaukee’s county jail under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

This federal law, enacted to appease Southern slaveholders, compelled free states to return escaped slaves, turning places like Wisconsin into hunting grounds for human prey that slaveholders considered property. Glover’s arrest could have been the end of his story—a quiet return to chains and a brutal existence—but it instead sparked a firestorm that rippled across the state and beyond.

By the next day, March 11, 1854, news of his capture reached Milwaukee’s abolitionist community, igniting a response that would etch his name into history. Sherman Booth, a fierce abolitionist and editor of the Wisconsin Free Democrat, leapt into action. Riding through Milwaukee’s muddy streets, he rallied a crowd that reports say swelled to over 5,000 outside the courthouse on what’s now Cathedral Square. Among the key figures were John Messmer, a local merchant, and James H. Pain, a lawyer, both vocal opponents of slavery who helped stoke the growing fury.

The throng demanded Glover’s release, but when federal authorities and Sheriff Charles E. Durkee refused, words turned to action. Led by Booth, the crowd—armed with pickaxes from a nearby construction site and a timber ram—smashed through the jail’s doors at the corner of East Kilbourn Avenue and North Jackson Street. Glover, still bruised from the beating he took during his arrest, was freed in the chaos, hustled into a waiting buggy by rescuers like A.P. Dutton, a shipping agent and Underground Railroad operative. From there, he was spirited back to Racine, hidden in Dutton’s warehouse on the harbor, and smuggled aboard a steamer to Canada in early April 1854.

After nearly 40 days on the run, Glover landed in Etobicoke, Ontario, where he’d live out his days, working for Thomas Montgomery and eventually owning land—a free man until his death in 1888.

The rescue wasn’t just a local uproar; it sent shockwaves through Wisconsin’s political landscape. Federal authorities, furious at the defiance, charged Booth and others, including Charles Watkins, a Black abolitionist who’d been part of the rescue, with violating the Fugitive Slave Act. The legal fallout dragged on, culminating in Ableman v. Booth (1859), where the U.S. Supreme Court upheld federal power. But Wisconsin’s response was bolder still.

The state Supreme Court, led by justices like Abram D. Smith, declared the Fugitive Slave Act unconstitutional in 1854, a radical stance that made Wisconsin the only state to openly defy it. This clash between state and federal authority didn’t just spotlight Glover’s escape—it fueled a growing abolitionist fervor that reshaped the region’s politics.

Nine days after the jailbreak, on March 20, 1854, a group of abolitionists gathered 90 miles northwest of Milwaukee in Ripon, Wisconsin, at a little white schoolhouse on West Fond du Lac Street. Among them was Alvan Earle Bovay, a New York transplant and fierce anti-slavery advocate who’d moved to Ripon in 1850. Bovay, joined by locals like Amos Loper, Jehdeiah Bowen, and Jacob Woodruff, had been incensed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act, introduced in January 1854 by Senator Stephen Douglas. That bill threatened to extend slavery into new territories, unraveling the Missouri Compromise of 1820. The Glover rescue, happening just as Congress debated this measure, poured fuel on their outrage. At the Ripon meeting, held in a clapboard building barely 20 by 30 feet, Bovay proposed a new political party to unite Whigs, Free Soilers, and disillusioned Democrats against slavery’s spread. They didn’t formally name it “Republican” that night—Bovay advised waiting—but the seeds were sown. By July 13, 1854, at a state convention in Madison chaired by figures like Edwin Hurlbut, the Republican Party took official shape, its platform cemented in opposition to slavery’s expansion.

Did Glover’s rescue directly spark the Ripon meeting? Not in a straight line—Bovay had been mulling a new party since 1852, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act was the primary trigger. But the timing and symbolism were undeniable and the altercation in Milwaukee was the final straw. The rescue, just 11 days earlier, electrified Wisconsin’s abolitionists, proving that grassroots action could defy unjust laws. It galvanized men like Bovay, Booth, and their allies—farmers, laborers, and immigrants—who saw in Glover’s liberation a call to organize. Historians argue the connection: the Glover incident “stirred public excitement to fever pitch,” as Henry Legler wrote in 1898, amplifying the anti-slavery sentiment that crystallized in Ripon.

The schoolhouse meeting wasn’t a spontaneous reaction to Glover alone, but his rescue was a vivid backdrop, a real-time lesson in resistance that emboldened the founders.

Glover’s saga didn’t end slavery—it took a war and over 600,000 lives for that—but it lit a fuse. In Milwaukee, Racine, and Ripon, ordinary people like Duncan Sinclair, who’d employed Glover, and Charles Durkee, later a Republican congressman, showed that defiance could shift history. The Republican Party, born in that tense spring of 1854, rode this wave, winning Wisconsin’s loyalty by decade’s end and helping elect Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Glover himself faded into Canada’s quiet fields, his body later lost to an unmarked grave after a medical school mix-up. Yet his escape, and the hands that freed him—Booth’s rallying cry, Messmer’s resolve, Dutton’s harbor hideout—carved their place in history. It’s a story of one man’s flight and a state’s awakening, a messy, human struggle that nudged a nation closer to reckoning with its original sin.

Source/Research Materials and Additional Reading:

Wisconsin Historical Society: “Joshua Glover: A Journey From Slavery to Freedom”

Detailed account with primary sources on Glover’s life and rescue.

Encyclopedia of Milwaukee: “Joshua Glover”

Focuses on the Milwaukee events and legal aftermath.

H. Robert Baker, The Rescue of Joshua Glover: A Fugitive Slave, the Constitution, and the Coming of the Civil War

Ohio University Press. Explores the rescue’s broader impact and Ripon’s role.

Ripon Historical Society: “Birthplace of the Republican Party”

Details Bovay and the March 20 meeting.

Henry Legler, Leading Events of Wisconsin History

Milwaukee: Sentinel, 1898. Early account linking Glover to political shifts.

DairylandSentinel: Five Fast Facts and Wisconsin and the Civil War