A century before people paid for water with labels like Evian, Dasani and Aquafina, consumers from across the globe shelled out money for water with a more prestigious name: Waukesha.

The year was 1893.

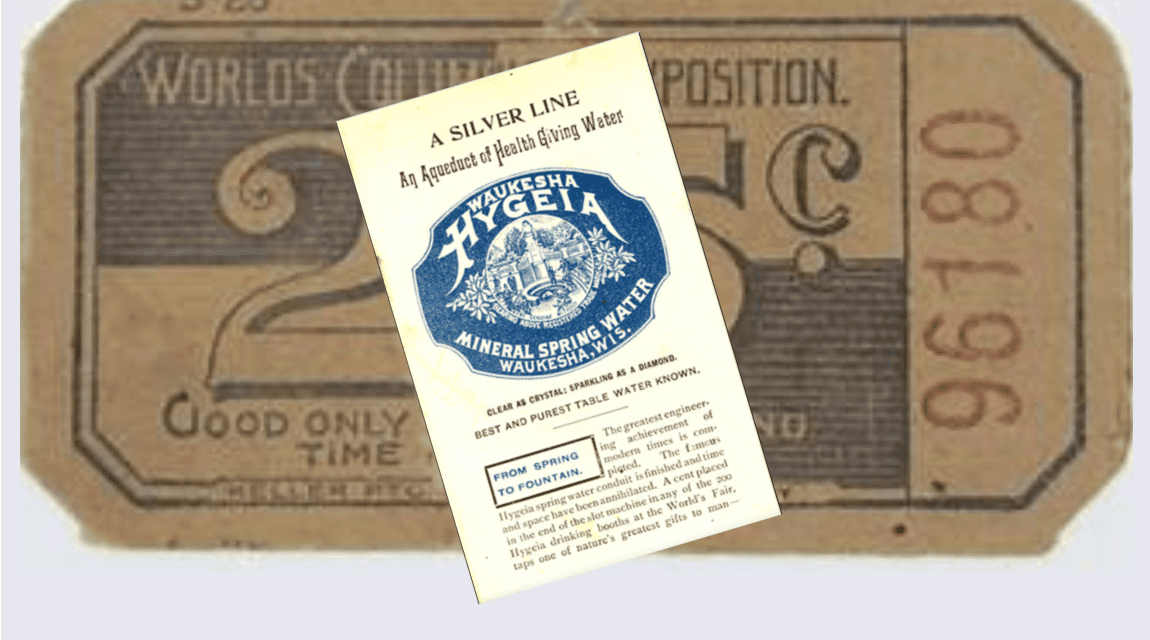

Waukesha’s water received a notable mention during the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago. This event, often referred to as the World’s Fair, was a significant cultural and commercial showcase, where Waukesha’s water was a subject of interest for its reputed health benefits.

The story of Waukesha’s water at the World’s Fair begins with the city’s rise as a health resort in the late 19th century, becoming known as the “Saratoga of the West.” This nickname was due to its numerous mineral springs, which were believed to cure a range of ailments from diabetes to depression. The fame of Waukesha’s waters was largely propelled by Richard Dunbar, who, after claiming his diabetes was cured by drinking water from a spring near Waukesha, began marketing it extensively.

By the time the World’s Columbian Exposition was planned, the reputation of Waukesha’s mineral waters had spread far and wide. Entrepreneurial spirit (a more polite way to say hucksterism) led to the idea of showcasing this water at the exposition. However, there was a twist: instead of merely exhibiting it, the plan was to pipe Waukesha’s pure spring water directly to Chicago for sale during the fair. This ambitious project was undertaken by piping water from what is now known as Hygeia Spring in Big Bend, about 10 miles closer to Chicago than Waukesha itself, which facilitated the logistics.

The water was sent through a pipeline and sold via automatic machines for a penny a glass at around 300 booths across the exposition. This not only served as a commercial venture but also as an exhibit of Waukesha’s natural resources. The fair ran from May 1 to October 30, 1893, attracting millions of visitors who could partake in the “cure” of Waukesha’s waters.

However, this venture was met with local resistance initially. In 1892, before the fair, there was an incident where local residents, fearing the depletion of their precious springs, confronted and repelled workers attempting to lay the pipeline. Despite this, the project continued, showcasing not just the water but also the engineering feat of transporting it over such a distance.

The World’s Fair exposure further cemented Waukesha’s reputation as a health destination, leading to increased tourism and development around its springs. The city’s waters were not just a local phenomenon but became nationally recognized, spurring the growth of hotels, bath houses, and other facilities catering to health tourists.

9.30.24