The tale of Paul Bunyan, the giant lumberjack, can be traced as far back as the winter of 1885-1886 at a logging camp near Tomahawk, Wisconsin. According to an account by the Wisconsin Historical Society, these stories were shared among lumberjacks and logging campers orally, with a man named Charles Brown learning them from a retired camp foreman in Oshkosh.. By the turn of the 20th century, tales of Bunyan had spread across logging camps from coast to coast.

The first documented mention of Paul Bunyan in print appeared in the Duluth Evening News on August 4, 1904, followed by more stories in the Oscoda Press in August 1906. These stories gained wider recognition when “The Outer’s Book,” a Milwaukee-based nature magazine, published them in February 1910 and then were reprinted in major newspapers like The Washington Post and the Wisconsin State Journal.

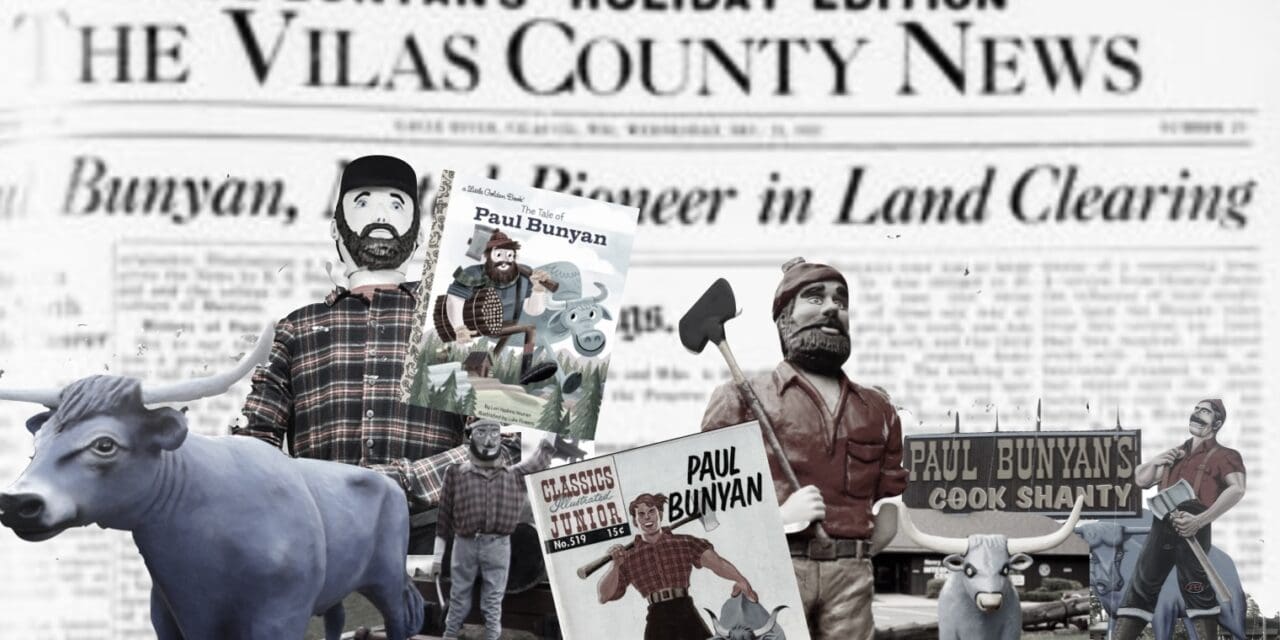

The Vilas County News published a special Paul Bunyan holiday edition of the paper in 1921.

The first books dedicated to Bunyan’s stories were promotional materials by the Red River Lumber Company of Minneapolis, published in 1914, 1916, and 1922. (cultural appropriation by our neighbors to the West?) Over the subsequent decades, they distributed over 100,000 copies, while author James Stevens also popularized these tales through his books.

By the 1940s, the stories had evolved so much with embellishments that folklorist Richard Dorson labeled them “fakelore.”

In their original form, Bunyan stories served multiple purposes in logging camps:

- Testing New Recruits: Veterans would spin tall tales to test the gullibility of newcomers, often teenagers unfamiliar with the logging life.

- Intimidation: The stories exaggerated the harshness of the environment to prepare or scare rookies.

- Entertainment: Storytelling was a form of entertainment where loggers would engage in “lying contests” to see who could tell the most outlandish tale.

The Wisconsin Historical Society shares a sample from a lumberjack near Butternut, Wisconsin, before World War I, showcasing the humor and hyperbole:

"As it has been so long ago since we logged on the Little Onion, I can't remember what the color of the snow was. I do remember, however, that it was so cold that winter on the Little Onion that your 400 below weather would have looked like the climate of the tropics beside it. It was so cold that words froze right in the air. All winter long the weather remained that way. If one said 'Hello' he could see it hanging in the air. If a teamster swore at his team, the sound of his voice would freeze also. That spring when the thaw came you could see all of those oaths thaw out the same day. Never in all history since the beginning of man was a more terrible profane barrage thrown over than there was that spring on the Little Onion."

The most authentic collection of Bunyan tales was compiled by K. Bernice Stewart and her professor Homer A. Watt from 1914 to 1916, published in the “Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Arts, Sciences and Letters” in 1916.

As logging gave way to tourism in the Northwoods during the 1920s, Paul Bunyan transformed from a figure of folklore into a symbol of an idealized past. His image was used in festivals, on statues, and in promotional materials across the U.S., symbolizing everything from the hardworking laborer to American might during WWII. Over time, Bunyan’s stories moved from campfire tales to children’s literature, embodying cultural values and becoming a widespread icon in American culture, with over 1,000 books mentioning him and more than 300 dedicated solely to his adventures.

He may be a cultural icon for many across the US, but his roots are in Wisconsin’s logging camps.